Following the Stonewall riot in 1969 the Gay Liberation movement spread from the United States to many other countries and found footholds within most major universities. [i] At Macquarie University Gay Liberation was to sink deep roots and one of the most important episodes in Macquarie’s radical history would take place around this issue.

Leading radicals on campus took the question of Gay Liberation quite seriously. Jeff Hayler was a gay student at Macquarie and a member of the Socialist Youth Alliance (SYA); he argued quite early on for the SYA to take the question of Gay Liberation seriously and gave an important talk on the topic that was published in the SYA paper Direct Action.[ii]

When Hayler ran for a vacancy on the Macquarie University Student Council (MUSC) in March 1973 a furious homophobic campaign was launched in the pages of the student newspaper, Arena, by Mark Aarons from the Communist Party. [iii] Mark Aarons was the editor of Arena and according to Peter Jamieson from the SYA ‘Aarons’ attitude to homosexuals seems to spring from the position of the Stalinised communist parties which hold that homosexuality is a degenerate product of capitalism.’[iv] However with the impact of the Stonewall riots in 1969, the Macquarie University Gay Liberation club giving confidence to gay students on campus and the sexually liberalised atmosphere being produced by the turmoil of the times these attacks resulted in a backlash from students and Jeff Hayler won his position. Mark Aarons eventually resigned so he didn’t have to face a motion of no-confidence. [v]

Hayler came into office just in time, for what occurred next is probably Macquarie University’s best known radical story. The victimisation of Jeremy Fisher by Robert Menzies College.[vi]

Jeremy Fisher was a gay student and resident of the Robert Menzies College; on the night of the 26th of May 1973 he tried to commit suicide. In hospital he was grilled by a psychiatric registrar who had been told by the university that Gay Liberation badges had been found in Fisher’s room. The article in Direct Action tells the next part of the story:

”Following an attempted suicide on Robert Menzies College premises by a resident of the college, Jeremy Fisher, the master of the college, Dr Alan Cole, discovered in his belongings that Fisher was treasurer of the Macquarie University Gay Liberation Club. When Fisher returned from hospital and had discussions with Dr Cole the question arose of Fisher’s commitment to gay liberation. Fisher informed Dr Cole that he was a homosexual whereupon Dr Cole insisted that Fisher repress his sexual preferences and seek help from someone prepared to assist him. Fisher was excluded forthwith from the college until he complied with these conditions.”[vii]

The fight was on. Fisher went to the Macquarie University Student Council (MUSC) and spoke with Jeff Hayler and Rod Webb, also a SYA activist, ‘I explained my problem with Robert Menzies College and they immediately went to work, ringing their contacts across Sydney.'[viii]

A demonstration was hastily arranged, MUSC started to campaign for the Robert Menzies College to be disaffiliated if it didn’t let Fisher back in and the Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) indicted support for the campaign. Also a Special General meeting of the Macquarie University Staff Association voted to support Jeremy Fisher. [ix] It was the support of the BLF though that would prove most important.

The BLF was a militant union that had fought tough industrial campaigns but also had used Green Bans to save important parts of native wildlife and working class housing in Sydney.[x] The BLF covered the workers who were completing some work on the Robert Menzies College and other sites on the campus including a lecture theatre, maintenance depot and a science workshop. Upon negotiations with MUSC the builders labourers working on Robert Menzies College went on strike in support of the demand that Fisher be let back into the college.

The move to strike in support of Jeremy Fisher was not without some hesitation amongst some within the BLF. Greg Mallory for instance writes that one of the BLF officials ‘Joe Owens related how he was approached by a builders labourer in a pub who asked, ‘what does your wife think about you knocking around with poofs, Joey?’ [xi] Meredith and Verity Burgmann also note that ‘Pringle [a leading BLF official] suggests the debate at the meeting that endorsed the ban indicated the unionists were more concerned ‘about the dictatorial attitude of the Master of the College rather than the actual issue of homosexuality’. [xii]

Be that as it may the meeting of the builders labourers’ at the university voted unanimously to support the ban [xii]. As Jack Mundey points out ‘I must admit that we were a bit apprehensive about this request. The BLF has discussed a lot of issues in recent years but the attitude of male superiority was still pretty strong, and there was likely to be a lack of understanding of homosexuals. Bob Pringle went out to North Ryde to explain the union’s policy to the workers on the site. To our surprise, the men on the job had no hesitation in deciding to go out on strike.’ [xiv]

It should also be noted how politically advanced this was for the time. Ideas around Gay Liberation were only just really beginning to become known to wider layers of people and this was five years before the first Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras in 1978.

Sometimes there was misunderstanding between Fisher, the radicals in MUSC and the BLF. The BLF however fully supported Fisher as a meeting between them recounted by Fisher reveals:

”The BLF assumed I wanted to return until, one day in the Students’ Council basement, Bob Pringle, part of the union’s leadership, asked me: “Why do you want to go back into that place?”

“I don’t,” I said.

“But we’re out on strike to put you back,” he said, a hint of anger in his eyes.

“I thought because I’d been kicked out for being gay,” I answered.

Bob looked at me for a moment, directly into my eyes. All sorts of thoughts whirled in my head. Was he going to withdraw the BLF’s support? Did he think I’d tricked him? Did he want to hit me? Then he said: “I guess you’re right. It’s the principle of the thing. They shouldn’t pick on a bloke because of his sexuality.” [xv]

In the end the BLF extended the strike to cover other buildings on campus and even threatened a full university ban. The action showed both how unions could take up ‘non-industrial’ issues in order to combat oppression which undermined working class unity and also how student radicals could reach out to the force in society which had real power to change things- the organised working class.

The legacy of this action continued to hold at Macquarie University, this was revealed by another case of discrimination at Macquarie University that started at the end of 1973. [xvi]

Penny Short was studying to be a teacher at Macquarie University on a teacher’s scholarship. At the time all teachers had to have a medical check. Short received a psychological test which then required her to get an assessment from a Health Commission psychologist. Before she left to see the psychologist Short was told that ‘you’re more aware of what’s happening in society, more perceptive of yourself and others and more individualistic — so you’ll have to have an interview with a psychiatrist to see whether you’re suitable to be a teacher.’ [xvii]

After being probed by the psychologist Short revealed that she was in a relationship with another woman. The psychologist told her to keep it quiet and that it wouldn’t be problem. However shortly afterwards Short had a lesbian poem published in the student paper Arena. She was brought back to see the psychologist who told her ‘you haven’t been keeping your homosexuality quiet, have you?’ Penny was then declared ‘medically unfit’ to receive the scholarship.

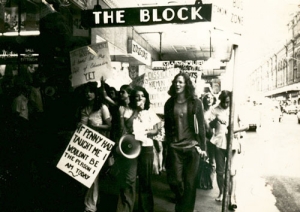

Student radicals at Macquarie sprang into action, organising Penny to do a speaking tour at Sydney University and UNSW. Between 600 and 1000 students attended a meeting at Macquarie University and voted for MUSC to support Penny. The Meeting was addressed by Short herself, representatives of the NSW Teachers Federation, and academics from the Schools of Education, Behavioral Science, and Historical, Philosophical and Political Studies [xviii]. Over 7000 signatures were gathered calling upon the NSW Teachers Federation to take action. At first they did, helping her organise a protest on March the 29th. The rally was over 1,000 people strong and marched through the city and to the Department of Education. However, afterwards, right-wing sections of the Teachers Federation bureaucracy moved to limit support and stop a joint press conference from going ahead. The BLF also endorsed the rally and according to Jeremy Fisher ‘The BLF leadership[‘s] attitude towards civil rights in general is distinctly better than that of the NSW Teachers Federation and in sharp contrast to the Department of Education’s attitude.’ [xix]

The BLF Secretary Joe Owens sent a telegram to the Minister for Education stating: ‘NSW Builders Labourers Federation condemns Education Department for discrimination against Penny Short. If scholarship is not returned, bans will be placed on maintenance work by builders labourers on Education Department buildings and other Government offices.’ [xx] Meredith and Verity Burgmann also point out that ‘many NSWBLF activists marched in the demonstration against the Education Department’s decision to suspend her scholarship.’[xxi]

Unfortunately Penny Short did not get her scholarship back, although she was allowed to be a teacher in 1987 after passing a Diploma of Education at UNE Armidale. [xxii]

Gay Liberation would continue to bear fruit for years to come at Macquarie, With students being organised by student radicals and the CPA to attend the first Mari Gras protest in 1978 that turned into a riot after it was attacked by the police. [xxiii]

Notes:

[i] For the beginnings of Gay Liberation see Sherry Wolf, ”The Birth of Gay Power”, Sexuality and Socialism: History, Politics, and theory of LGBT Liberation, 2009, pp. 116-136 and Neil Miller, ”Stonewall and the Birth of Gay and Lesbian Liberation”, Out of the Past: Gay and Lesbian History from 1869 to the Present, 2006, pp. 335-365. For the Gay Liberation movement in Australia see Liz Ross, ”Riots, rallies and resistance: the birth of Gay Liberation”, Socialist Alternative, 24 May, 2012.

[ii] Jeff Hayler, ‘’Gay Liberation: A Talk by Jeff Hayler’’, Direct Action 43, 28 June, 1973, pp. 20-21.

[iii] See Peter Jamieson, ‘’Students Defend Gay Liberationist at Macquarie’’, Direct Action 38, 29 March, 1973, p.4 and the March 13 1973 issue of the Macquarie University student paper, Arena.

[iv] Jamieson, ‘’Students Defend Gay Liberationist at Macquarie’’, p.4. For an explanation of the connection between Stalinism and homophobia see Sherry Wolf, ”Stalinism, Maoism, and homophobia”, Sexuality and Socialism: History, Politics, and theory of LGBT Liberation, 2009, pp. 100-104. It should be noted that by this time the Communist Party has actually moving to the left and in particular was orientating towards the gay liberation and women’s liberation movements. Why Mark Aarons went against this trend, at least during this period, is unclear.

[v] Jamieson, ‘’Students Defend Gay Liberationist at Macquarie’’, p.4, MUSC Chairman’s Annual Report, Arena July 1973, Vol.6 No.8, p.8.

[vi] The following account comes is based upon: ‘Robert Menzies College: Support Action Against Oppression’, Arena July 1973, Vol 6 No 8, front page, Peter Jamieson, ‘’gay student victimised’’, Direct Action 43, 28 June, 1973, p.6. Meredith and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union: Environmental activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers’ Federation, 1998 pp. 141-143. Jeremy Fisher, ‘religious persecution’, CAMP Ink V3 N5 1973. Jeremy Fisher, ‘’Into the Light’’, Overland 191, 2008 pp. 52-56. Grey Mallory, Uncharted Waters: Social Responsibility in Australian Trade Unions, 2005, pp. 128 -129.

[vii] Peter Jamieson, ‘’gay student victimised’’, Direct Action 43, 28 June, 1973, p.6.

[viii] Jeremy Fisher, ‘’Into the Light’’, Overland 191, 2008, p. 54.

[ix] Arena, July 1973, Vol 6 No 8, pp.4

[x] See Meredith and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union: Environmental activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers’ Federation, 1998

[xi] Grey Mallory, Uncharted Waters: Social Responsibility in Australian Trade Unions, 2005, p. 129.

[xii] See Meredith and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union: Environmental activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers’ Federation, 1998, p. 142.

[xiii] Meredith and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union: Environmental activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers’ Federation, 1998, p. 141.

[xiv] Jack Mundey, Green Bans & Beyond, 1981, p.106.

[xv] Jeremy Fisher, ‘’Into the Light’’, Overland 191, 2008, p.54.

[xvi] The following account is based upon: Jeremy Fisher, ‘’Gay trainee teacher victimised’’, Direct Action, April 1974. Penny Short, ‘’How I lost my scholarship’’, Arena, 27 March, 1974. Grey Mallory, Uncharted Waters: Social Responsibility in Australian Trade Unions, 2005, pp. 129-131.

[xvii] Penny Short, ‘’How I lost my scholarship’’, Arena, 27 March, 1974

[xviii] Grey Mallory, Uncharted Waters: Social Responsibility in Australian Trade Unions, 2005, p. 130.

[xix] Jeremy Fisher, ‘’Gay trainee teacher victimised’’, Direct Action, April 1974.

[xx] Grey Mallory, Uncharted Waters: Social Responsibility in Australian Trade Unions, 2005, p. 131.

[xxi] Meredith and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union: Environmental activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers’ Federation, 1998, p. 142.

[xxii] from the postscript to Penny Short, ‘’How I lost my scholarship’’ online at http://www.pridehistorygroup.org.au/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=104&Itemid=1

[xxiii] See Jeremy Fisher, ‘’Into the Light’’, Overland 191, 2008. Peter Murphy, ‘Building up to Sydney’s first gay and lesbian Mardi Gras’, Vintage Reds: Australian stories of rank and file organising. Radical Sydney

Pingback: Welcome | Radical History of Macquarie University

Thanks for your article GAY LIBERATION AT MACQUARIE re Jeremy Fisher and Penny Short.

I was a little distracted by the reference to “a furious homophobic campaign… launched… by Mark Aarons from the Communist Party”, referencing “the position of the Stalinised communist parties which hold that homosexuality is a degenerate product of capitalism”. Glad this was somewhat moderated in footnote (iv), as within a year the CPA had formally denied such a line:

“The Communist Party totally rejects the view that homosexuality is a “disease” of decadent capitalism which socialism will “cure”. The Communist Party affirms that what is wrong with capitalism is, rather, that it oppresses homosexuals. It rejects the view that the continuation of homosexuality under socialism is a capitalist “survival” that must be eliminated.” (COMMUNIST PARTY OF AUSTRALIA 24th NATIONAL CONFERENCE. Resolutions Adopted. June 1974 http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:hxvPh-sA67kJ:www.anu.edu.au/polsci/marx/gayleft/doc_on_h.rtf+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=au )

Indeed later in the 70s, Gay Men’s Rap and some lesbian groups were welcome users of the CPA conference centre at Minto, managed by former General Secretary of the CPA (and Mark’s father) Eric Aarons. Of course we had an effective advocate within the party in Brian McGahen, a trustee of the Minto property.

I’d be interested in any online documentation of Mark Aaron’s vitriol in Arena. But regardless, thanks for the discussion.

Hey Gary,

Thanks for the comment.

Yeah as I say in the footnote it is unclear why exactly Mark Aarons went on this particular bent, the reference to the positions of the Stalinist communist parties comes from a Trotskyist student activist from Macquarie at the time. But as you point out the CPA already had an orientation against homophobia. I don’t know enough about the internal dynamics of the CPA at the time – and Mark Aarons place within it – to give a fuller explanation of where his attitude came from.

Aaron’s editorials and the responses aren’t online unfortunately, they can be found throughout the 1973 editions of Arena which can be found at the State Library of New South Wales.

– Jordan

Pingback: My union marched with Pride | We won! But the battle's not over

Pingback: Jack Mundey: Gay and Lesbian Rights | tradeshall